Absurd fantasies & Refexive De-Constructions:

a genealogy of my aesthetic from films.

Almost every movie I love falls into two categories: high camp absurdism or inter-textual counter-cinema; sometimes, these overlap; sometimes they oppose one another, with varying desire to appease the pleasure principle (even “In the Mood for Love” is an endurance test for me). What follows is a list, in no particular order, of the films I’ve revisited as testaments to pleasure and un-pleasure. Cinema as experimentation, cinema as completely proud pastiche….

Hal Hartley’s Flirt (1995)

We’re using the same language I use to lie to him…

Parker Posey realizes aloud, nude in a New York City studio apartment, setting up the whole crux of this sweet philosophical experiment. “I want you tell me if there’s a future for us / you don’t have to see it to know its there,” she commands Bill, who must giver her an answer by 5 o'clock when she flys to Paris, France. At his local dive bar, he’ll consult a Brechtian chorus in the men's bathroom: it’s important to keep the girl in your influence at all times! and: the best of all possible approaches to this dilemma is for the both of you to firmly embrace reality!

Like all Hartley films, the dialogue is delivered in a style simultaneously tender and staccato; a language simplified like song lyrics, somehow both ambiguous and piercing. This story cycle repeats verbatim in Berlin and then Tokyo—the German version with a gay interracial fashionista and the Japanese tale told entirely in silent Butoh. If it sounds overly pretentious, don't worry, Hal already knows: "The filmmaker wants to ask if the same situation played out in different times amounts to anything different," a construction worker ponders in second person in somewhere-platz, "but he's already failed."

Success, humility, failure, or good filmmaking: it doesn't much matter. Hartley has stated that this is his favorite of his films. It’s personal: it ends with a shot of him holding a canister of 35mm motion picture film, labeled "Flirt,” collapsed and despondent from the act of repeating and constant movement. But, he's found by Miho Nikaido, the Japanese protagonist, who later becomes his wife...you know, in real life.

Mood: open-hearted, wondrous, everything-is-gonna-be-alright

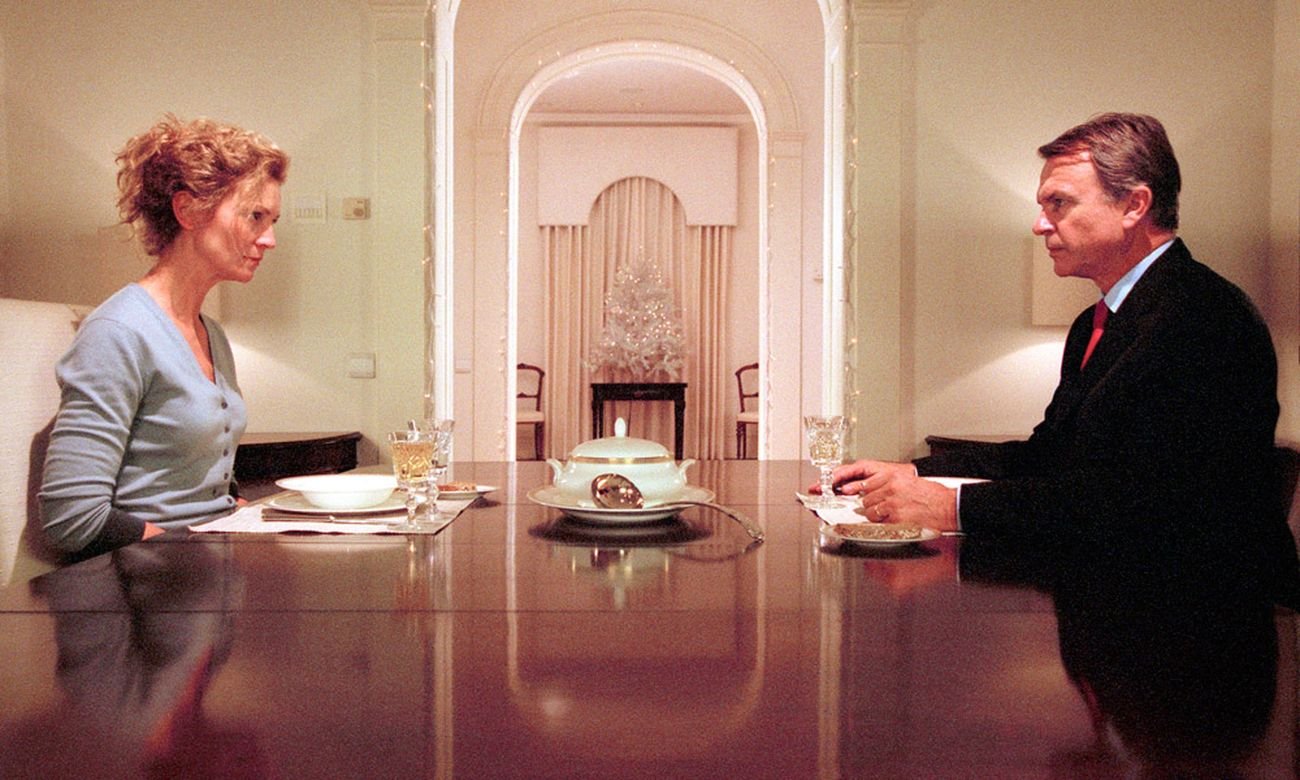

2. Sally Potter’s YES (2004)

Sally Potter started to write YES on September 12, 2001. Flipping the Hollywood spectacle of the romance film, it is a meditation on how we understand our subject positions (gender, nationality, religious, political) told entirely in iambic pentameter; for this, it has been ruthlessly mocked as trying to be overly artsy. I believe the language flows seamlessly; seemingly more distracting are the very early 2000s cinematography choices (the diagonal angle, the shaky hand-held with jump-frames, and stop motion blurs) but these choices do serve as post-structural critique, inviting spectators to question the narrative and production.

She—as her name is never revealed—is an Irish-American scientist; He was a doctor in Lebanon but now uses knives in restaurant kitchens. They say Yes to each other while her marriage is collapsing; she’s in a gala-gown and he’s in a waiter’s suit, clowning and catching her giggles. Later, he fingers her in a cafe while she repeats yes, yes, yes. Let all things hidden be exposed. Yes. Let all things become pleasure. Yes. I’m going to make you cum. Yes.

There is an incredible scene where she visits her grandmother in Belfast, an old unconscious radical who telepathically commands her grand-daughter I want my death to clean you out! The film was made between 9/11 and the American invasion of Iraq; and, there’s this strange moment in the “making of” short film that’s always haunted me: the two main actors are with director Potter going over lines when suddenly, Joan Allen (She) breaks down crying about Bush’s press conference—the launch of the war against Saddam Hussein. Allen is crying out of (American) guilt, Potter consoles her, while Simon Abkarian (He) is stranded.

Mood: calamitous global politics don’t have to stop us from loving, but what are the limits of romantic solidarity anyway?

3. Atom Egoyan’s Calendar (1994)

“Only Armenians know this movie!” an Armenian Turk told me. But, Egoyan is Canadian-Armenian, with equal emphasis on both, as so much of his filmography is about the tension of being in a diaspora, and the lengths people go to feel belonging.

Egoyan seamlessly weaves themes of digital (dis)connection, diasporic loss, sex work as psychological therapy, and the use of repetition as (un)comfortable catharsis. The protagonist is deeply masochistic, continually devising a form of cuckolding not based in fucking, but a much deeper addiction to cultural alienation.

Mood: doesn’t it feel so right to watch your wife fall in love with someone else, you sub, nostalgic lil’ bitch

4. Jonathan Demme’s Rachel Getting Married (2008)

This is such an Obama-era movie. How can I back that up? See the upper-“middle class” East Coast family all dressed in Indian Saris for a cross-cultural wedding; gathering and not fighting about politics. They have enough trauma to wade through as Anne Hathaway’s character, Kym, cannot forgive herself for an accident that ripped the family apart years ago. This is one of the most honest representations of 12-step processes I’ve ever seen. This is also exactly how most weddings in my community feel: artistic family reunions. Also: Anna Deavere Smith can do anything and I am captivated.

I saw this in high school and it also introduced me to the genius musician Robyn Hitchcock, who I’ve now seen live twice.

Mood: what if your wedding vows were Neil Young lyrics?

5. Patrice Chéreau’s La Reine Margot (1994)

Based on a novel of the Saint Bartholomew’s Days Massacre by Alexander Dumas, La Reine Margot features Isabelle Adjani as Marguerite de Valois, forced into a fake-peaceful marriage to unite the Huguenots and the Catholics in 16th century France. The real star may be Catherine de Medici, played like a great literary villain. But, it should be noted that Catherine was well celebrated for her festivals that are unmatched and maybe unimaginable today; the film tries to express this lavishly. The love story between de Valois and the hot plebeian-Protestant was expanded for the U.S. release, including a scene of sweet-nothings along a countryside creek; this reminded me of the European alternative ending of Pretty Woman wherein the whore and the John go their respective ways; Americans have been so catered to in their delusions.

The score by Goran Bregović is incredible, bringing an oddly refreshing Eastern European feel to the stale form of the French period piece.

Mood: everyone is power is a pervert

6. Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz (1979)

How dare you call another man on my phone who’s not gay!

Inspired by Fosse’s own heart problem that kept him bed-ridden, the protagonist of All That Jazz is addicted to 3 things: amphetamines, cheating on his wife and girlfriend, and choreography. A time-capsule of the 1970s New York Broadway scene is also a musical about (ego) death with Fellini-esque motifs. Jessica Lange stars as the seductive angel of death taking Joe Gideon on a tour of his trauma, pleasures, and haunting mistakes. This is my mom’s favorite movie, who shared it with me at probably too young an age.

Mood: a dark cabaret dance number about an airline specializing in emotionally-empty orgies; “our motto is, we take you everywhere but get you nowhere.”

7. Gregg Araki’s Nowhere (1997)

Lucifer, you’re so dumb you should donate your brain to a monkey science fair!

This film has been a litmus test for anyone I’ve dated; if they didn’t get it, I knew things would be hard down the line. I’ve gone to some version of Juji-Fruit’s party so often in New Orleans, and even though this is an exploration of teenage (queer/punk) desperation in the ‘90s, it feels very true to my contemporary life in Louisiana. The protagonist Dark is looking for a more traditional love in this mess of poly-traumatic-high-saturated-horror mediated via some late night 1-900 ad or just static colorbars. Araki’s ending asks if radical subcultures are any less Kafkaesque than the “normie” world. The set design and art direction by Patti Podesta is a constant inspiration.

Mood: hey, shouldn’t you be in thermo-nuclear catastrophes class?

8. Scott Campbell’s Off the Map (2003)

Everybody gets depressed, why should you be above it, huh?

As much shit as I talk about Albuquerque, the truth is that New Mexico, the land itself—the way the sun hits without diffusing humidity, the smell of piñon burning in winter, and the endless sky—is incredibly magical. Off the Map is the film that epitomizes that beauty, showing how this landscape affects the social human realm. Based on a domestic-based theater piece, it’s a memoir of young Bo, a precocious girl who cannot wait to shed her rural poverty and be an office worker with a briefcase (and, one not from the dump). Joan Allen is the star; holding the piece together effortlessly as embodying a subtle indigenous grounding to their communing with the land.

Mood: human beings are part of nature

9. Michael Haneke’s Code Unknown (2003)

Montre-moi ton vrai visage!

Haneke is a master of the long take. He explains this in a making-of segment for The Piano Teacher, saying that it gives actors the space to play out a scene fully, and allows them to ride the wave of an emotional process fully. He repeats these takes mercilessly until the actors do something that surprises themselves—a shriek, a gesture from out of nowhere, a completely improvised action.

Code Unknown opens with a group of deaf children playing charades. Then, a long take on a Paris street that ends with the arrest of a North African and the deportation of a perceived Romani woman. The film continues on fragments of these characters from this single shot. There is a character—the war photographer—based on Luc Delahaye, the father of my friend, Mathilde Delahaye (an incredible theater-maker, herself).

Mood: we are all implicated in power structures; we are all responsible even if we want to believe our innocence

10. Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s All About Eve (1950)

“I walked into my dressing room and said “Good morning,” and do you know what [Bette Davis] said back to me? “Oh shit, good manners.” I never spoke to her again—ever.” —co-star Celeste Holm.

“Working on All About Eve was a tremendously enjoyable experience—the only bitch in the cast was Celeste Holm.” —Bette Davis

What can I say? I am super gay. And the script for All About Eve basically invented the catty queen, every line is just so juicy and satisfying. Part of a series of 50s flicks that questioned “the golden age of”—in this case, theater—it was a radical piece for its time.

Mood: every word of my seething breakdown will be a-nun-ci-ated, darling.

11. Gurinder Chadha’s Bend It Like Beckham (2002)

“Get your little lesbian feet out of my shoes!” / “Lizbian? I toaught she vas a Pisces!”

It’d be lying if I didn’t include this feel-good movie made almost entirely of musical montages of early 2000s club hits; Now That’s What I Call Cultural Understanding Vol. 4 — some previous South Asian-white (gay) romance hits being Chutney Popcorn (1999) and My Beautiful Laundrette (1985). It’s a shame that the original lesbian overtones were erased; but the inclusion of the hollow romance with Jonathan Rhys-Meyers is really gay in some odd way. Probably one of my all-time favorite bad movie lines is when he tries to console protagonist Jesminda after she receives a racist slur: “Jess—of caurse I know how that feels! I’m Ay-rish!”

Mood: Me? Kissing? A boy!? You’re mad, you’re all bloody mad!

12. David Cronenberg’s eXistenZ (1999)

“I have to play eXistenZ with somebody nice. Are you nice?”

Once you get through the longest opening credits sequence since 1959’s Ben Hur, you’ll find yourself in a small town rec-center where Allegra Geller is unveiling her brand new virtual reality video game. Everyone is porting into the fleshy console through their bio-port, a small opening at the bottom of their spines. “Death to the Demoness, Allegra Geller!” Suddenly a young boy shoots Geller with a gun made of teeth while she’s minimally conscious of “reality” — as much a statement of how consumer-media affects our sense of self and surroundings, the dialogue is also an implicit critique of Hollywood script structures. It was inspired by the declaration of fatwa on Salman Rushdie; and it’s probably the first time “non-playable characters” were poked fun of. Pay attention to Geller’s hair.

Mood: am i in a coma? did i win the game? did i win?

13. Ken Russell’s Crimes of Passion (1985)

Trailer narrator: “Never before have two adults consented to so much.”

I struggled to pick just one film from Ken Russell—the trashier English Federico Fellini who I truthfully love more. There’s the respectable “Women in Love” from 1969, incredible with Glenda Jackson; there’s his response to Julia Roberts in Pretty Woman with 1991’s “Whore,” a second-person monologue about the reality of sex work; there’s his outlandish musical bio-pics of Tchaikovsky and Mahler. I landed on Crimes of Passion simply because it includes a husky voiced Kathleen Turner introducing herself as “China Blue” while a red light constantly flashes in her nasty in-call space. There’s a priest with a metal vibrator that becomes a dagger. It’s Russell at his most sexually absurd.

B-Side (or honestly the A-side): Kathleen Turner in Body Heat.

Mood: Anthony Perkins can only play psychos, but this time there’s good good steamy sex and dildo murder

14. Ming Tsai Liang’s The Hole (1999)

The Hole makes claims about intimacy by subtracting it completely; the only relief in this abysmally depressing grey cloud of a film are musical numbers of Cantonese covers of 1950s American songs. A pandemic has shut down Taiwan; two apartment tower dwellers (minimally) deal with one another while a hole grows larger and larger between one’s floor and another’s ceiling. Tsai Liang is a master of slowness; he once filmed someone crying for half an hour; this piece is as relaxing as it dis-affecting, and totally dissociative.

Mood: in the mood for love, minus the love, minus the mood. add the smell of mold.

15. Cameron Crowe’s Vanilla Sky (2001)

“I almost died, and you know what—your life flashed before my eyes.”

As much as I would like to say I enjoyed Alejandro Amenábar’s original 1997 film “Abre los Ojos” more, I just didn’t. Maybe it’s because I’m a maximalist, maybe it’s because the inclusion of hyper-pop-culture made different statements here, maybe it’s Crowe’s overly sentimental style—it’s certainly not because of Tom Cruise. But, honestly, he does a good job here. This was one of my favorite films when I was a teenager, so even if I should abandon it for more high-brow selections, I’ve just seen it too many times to not acknowledge it’s influence on me: for one, maybe it is Julie Gulianni I eroticize as I’ve fallen for femme after femme fatale who threaten to take me on their suicidal plans; I certainly hope I will wake up at any moment, but while I’m here, the soundtrack is pretty great.

Mood: what do you think of my music? it’s vivid!

16. Sophie Muller and Annie Lennox: Diva (1992)

“Now, everyone of us is made to suffer! Everyone of us was made to bleed!”

Is it a stretch—including one of the first video albums? I don’t care: I have to credit Sophie Muller’s stunning filmography of music video production and her collaborations with so many 90s feminist icons—Lennox, Courtney Love, Gwen Stefani, Sinead O’Connor, PJ Harvey. She was inventing forms of femininity that were mediated out through MTV, adopted by young women across continents. In this huge achievement for Lennox’s first solo album, the two craft personas and poke up at the production of persona, either as pop star, lover, home-maker. They had already worked together creating the video album for the Eurythmics album Savage; that work is also incredible, but it didn’t get into me when I was a child like this one did (thanks, Mom).

Mood: it’s called diva

17. Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust (1991)

Its very rare that any film-maker gets to accomplish their dream project as a first feature, let alone a woman, let alone a black feminist who was Charles Burnett’s contemporary. Narrated by the future daughter of one of the protagonists, the film is a lyrical and impressionistic telling of the Gullah people in the early 20th century, when the pressure to move to the mainland (not coastal South Carolina, but towards Chicago and New York) was strong. Even though the community retains a near-total control and black autonomy on their islands, they are still haunted by slavery, colonialisms, and threats to their livelihood. Dash was clearly aesthetically influenced by Peter Weir’s “Picnic at Hanging Rock” from 1975—and they do have a strange kinship, even though Weir’s entire cast is lily-ass white, the film is just as haunted by colonial ghosts and the power of land to (take) hold of us.

Mood: soul-affirming, family bonds as historical struggle

18. Harvey Feinstein’s Torch Song Trilogy (1988)

I think my biggest problem in life is being young and beautiful. Oh, I’ve been beautiful! God knows I’ve been young—but never the twain have met…

This is a gay touchstone for me; it’s the romantic comedy turned tragedy turned fights with Jewish mother movie I needed to understand what queerness past might’ve been like. The film is based on Feinstein’s play from 1982 which mostly chronicles gay life of the 1970s, hence why HIV makes no cameo in this story. There’s even an acceptance of bi-sexuality, certainly not a common practice then by gay male scenes; Matthew Broderick is the no-drama boyfriend every queen desperately needs and doesn’t deserve.

Mood: heart-warming; family is not based in blood-ties

19. Pedro Almodovar’s Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988)

Take me back to the hospital, that's my home!

I make a really great gazpacho; it’s not at all the recipe from this movie that is recited maybe 12 times. It’s actually more of a salmorejo: a smooth creamy emulsion of tomato and olive oil with sherry vinegar, sugar, salt, and smashed garlic with stale bread. Once, I made it for a dinner party and a friend said “You are so fucking gay, I can’t handle it!” So, here’s to the gays and our gazpacho! At least my party didn’t culminate in multiple barbiturates, forlorn love triangles, and a twiggy-brunette holding a gun to our heads. This is Almodovar giving himself full permission to be a high camp queen.

Mood: wigs on motorcycles with guns

20. John Greyson’s Lilies (1996)

Forgive me, Father—I’m about to commit the sin of revenge.

I have more than a high tolerance for experimental productions resulting in less-stellar works. Like Sally Potter’s “The Gold Diggers,” which was the only film to be made entirely by women and explored inter-race/class feminism, “Lilies” is made entirely by gay men. “Lilies” comes after Greyson’s musical about the HIV crisis, “Zero Patience,” in which Sir Richard Burton is brought to contemporary times to stage an anthropological exhibition on the AIDS “patient zero.” Greyson would later be imprisoned in Egypt for preparing work on a film centering Gaza activism; this is all to say: Greyson is a film-maker comrade. And, with “Lilies,” he let that militancy relax slightly to create a theatrical period piece mise en scene akin to Marat / Sade. He still wants to light the Catholic church on fire, though there is a conclusion of mutual understanding.

Mood: a gay man in drag as Julie Taymor does shadow puppets in prison

21. Jean-Luc Godard’s Notre Musique (2004)

Isn’t it time for us to meet face to face — both of us strangers in a strange land!

In this dense essay film of three parts—“Hell,” “Purgatory,” and “Heaven”— Godard traces elements of (mediated) violence, akin to his Austrian contemporary Haneke, but with flashes of Brechtian staccato and Deleuzian film theory. In the longer central section, a student is attending a conference on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict hosted in Sarajevo, itself a site of recent atrocities. There is a scene of American natives, the image of them in excessive Plains-Indian regalia, interjecting their subjectivity and loss of place within a history of genocide inside a bombed out Bosnian library that remains with me forever.

Mood: a degree in film studies within 90 minutes

22. Alfonso Cuarón’s Y tu mamá también

The truth is cool but unattainable…the truth is totally amazing, but you can’t ever reach it.

This expansive wide-angle film is undoubtedly the progeny of Godard: with its omniscient anonymous narrator interrupting throughout, elucidating macro social critique based on the characters’ navigation of inter-class dynamics within Mexican daily life. Cuarón might have been more epic with “Roma,” and he may have achieved greater world-building and camera work with “Children of Men,” but this is him holding compassion without empty charity: the subtle violence of socio-political structures in bright sunlight.

Mood: a geyser of cum falls into a private pool somewhere in Polanco

23. Rosa Von Praunheim’s City of Lost Souls (1983)

I fell in love a Russian soldier! We go marching through a park! I just love Karl Marx!

Once you see Jayne Country holding up her fist and pledging allegiance to communism with overly saturated hot pink cheekbones and blown out ‘50s blonde hair, you understand immediately the origins of John Cameron Mitchell’s Hedwig. I believe strongly in homages that bring an audience to life-source, and City of Lost Souls is certainly an ecstatic oasis worthy of a pilgrimage. Within a Berlin-based Cockettes-esque commune, a group of queens, transexuals, weirdos, and depressives labor at “Burger Queen” by day and orgy by night, all narrated by the overbearing Americans at the squat, speaking elementary German. This is quasi-documentary, giving voice and tender humanity to race and gender politics of the era. It is holy.

Mood: the gay who didn’t finish film school

24. Harvey Keith’s Mondo New York (1988)

Outcasts! Losers! Perverts! Lunatics! Psychotics! Maniacs! Brainiacs! Hippies! Yippies! Yuppies! Junkies! Flunkies! …Monkeys! All tryna claw their way to the top of the trash heap!

This is the New York-No Wave companion to Praunheim’s piece; but, that doesn’t mean it’s a good film. It is however a great document of late 80s New York performance art scenes (Joey Arias, Karen Finley, Phoebe Legere, Dean Jonson and the Weenies). The hilariously stale framework is to follow a speechless hot normie blonde girl (proto-gentrifier) as she mostly wanders the streets of the Lower East Side, stumbling on all the identifications Lydia Lunch lists as a prologue. Watching this film in my late teen years (a VHS interlibrary-loan) gave me a hunger for wild artistic community that invited all levels of absurdism; it introduced me to performance art, initiating a whole livelihood. (Continue with Annie Sprinkle’s green-screen masterpiece, Orgasm!)

Mood: make deadly snow-balls out of the crumbling cement city-scape; this one has old cum and stray paint on it

25. Abel Ferrera’s The Addiction (1995)

What the hell were you thinking? Why didn’t you just tell me to go—Why didn’t you just say “get lost!” like you really meant it?

You have to brave The Worst Song Every Written for a Film that opens this masterpiece, another nighttime New York saga. One wonders what blackmail the songwriter had on Ferrera, because the rest of the soundscape is immaculate: Cypress Hill’s “I Want to Get High” being a great gritty refrain throughout. This is Lili Taylor giving a masterclass in losing it: a PhD student who implodes in philosophical psychosis after she’s bitten by a vampire within the first 3 minutes. She’s rotting from the inside, just like this whole desperate Empire, and she’s taking everyone with her. The lush black and white cinematography is the cherry on top of Christopher Walken playing the mansplaining holier-than-thou reformed addict who can intellectualize his momentary indulgences.

Mood: you seduced your philosophy professor, but then you killed him, and then you ate him. it was all so Hobbsian, but you Kant take it back now: face it, you’re a killer.

26. John Guillermin’s Death on the Nile (1978)

Oh, the crime passionnel, the primitive instinct to kill, so closely allied to the sex instinct!

For me, there is no other Hercule Poirot than Peter Ustinov: the disheveled and awkward pomp who manages to get everyone assembled poised in some splendid parlor, wade through every possible who-done-it until coming to the (well accented) denouement. This should be viewed along with “Evil Under the Sun,” but the high femme ensemble cast is just so amazing here, including Mia Farrow, Maggie Smith, Bette Davis, Angela Lansbury, and Jane Birkin. It makes perfect use of its on-location filming with the white world’s obsession with Egypt in the 1920s.

Mood: let’s go take a tip-toe swim in a full-body wool tunic and a colonial explorer sun-hat.

27. Anna Biller’s A Visit from the Incubus (2001)

But your soul, Lucy! The Incubus also feeds on your soul, you must not forget that!

I recently wrote to Anna Biller on her outdated website, sharing my portfolio and basically saying: anytime and anywhere, I want to support you on your art. To my disbelief, she replied (said she’s keep in mind for a future production). Biller makes her own sets; she hooked a circular rug with esoteric symbols on it for a shot lasting 20 seconds; she sews her own costumes; she writes the films as well as many original musical numbers in them. Her primary curiosity is “the glamor” and artifice of ‘60s and ‘70s films coming out of California: whether it was Hollywood, Russ Meyer, or 16mm television Westerns. Incubus is the latter, and even the poorly recorded audio hisses with its era. Is recreating these visions a feminist act of revisionist repetition? Maybe, Biller shrug-winks.

Mood: you can have diamonds! you can have rubies! you can have great big Boobies!

28. Zeina Durra’s The Imperialists Are Still Alive! (2010)

What’s the use in remaining chic if the government can disappear you at any moment? Durra puts a faux-verite spotlight on the cool kids’ underground Lower East Side during the islamophobia and extra-judicial kidnappings of the Bush aughts. Danger barely simmers under the surface boredom of these privileged youths; perhaps the best expression of hipsterism I’ve ever seen, and one that doesn’t chide the character’s positions. As spectators’, we are provoked in our own desires for a care-free romantic comedy that cannot be.

Mood: America is still land of the (care)free if you’re not in an FBI database

29. Leo Carax’s Lovers on the Bridge (1991)

As a kid, I had this thick-spined floppy book on ‘90s cinema. It totally enthralled me, especially the images it contained from this film. And though it would take a decade for me to actually find this DVD, I watched it incessantly so long as I had a disc drive. Later, I found out that Carax, in a complete fit of over-inflated genius, was not granted permission to actually film on the Parisian bridge (Pont Neuf) of which the film is centered; so, he built his own in some French countryside, complete with a whole hollow skyline. Then he recreated the firework display from the country’s tricentennial. Not taking No as an answer may be a form of insanity; but here, I am so grateful.

Mood: Monumentality unquestioned.

30. Sally Potter’s Orlando (1992)

You Sir prove to show it: while every poet is a fool, every fool most certainly is not a poet!

The only feature Sally Potter had made prior to Orlando was “The Gold Diggers” a decade earlier: a highly experimental production wherein Potter only hired women; it was beyond the mainstream feminist debates of its era when it featured a black immigrant rescuing a Gone With the Wind heroine from out of the cinema screen; the two are forced to contend with their representational relationality. Potter is my favorite film-maker not because everything she has done is great, but because her projects are committed to investigating her imaginations as filtered through media: whether musically, the filmic, or the digital (though she is also a brilliant dancer). In Orlando, she lavished Virginia Wolf’s gender-bending love-novel with appropriate bravado. Of course, Tilda Swinton is spellbinding, but its also Potter’s original score, her attention to cinematic choreography: the motion of bodies, camera movement, and cutting all a part of the dance. The film ends—and this hardly a spoiler—with Orlando’s young daughter toying with a Hi8 camera, filming Jimmy Sommerville floating in the sky like Walter Benjamin’s Angel of History, singing: “In this moment of unity, feeling, and ecstasy / to be here, to be now / at last I am free!”

Mood: gender is a construct; the soul is cosmic; Tilda is a (benevolent) alien