rio, arroyo, river (repeat)

three artistic prompts for dirty rivers

a.r. havel with Vanessa Norton and Shannon Stewart

I: basura, lavadoras, colchones y cachorros

The locals simply call it “el rio.” In some spots, it foams heavy with the bubbling scent of fabuloso, in others, its muddy cliffs are saturated in the sludge of sewage. From the wraught iron gates of the colonial hacienda in Xolostoc, it’s a 40 minute walk to the edge of Tlaxco, population of some 40,000. That’s if you take the red gravel road; if you follow el rio, it’s a meandering hour and a half, give or take some time for troubleshooting how to side-step feces, trash, and sporadic rock rapids.

For twenty days, I walked along this river, this dirty little arroyo, as a plea for sanity. In said colonial hacienda, I was among thirty-five artists, curators, and theorists, gathered for an intellectual symposium on the topic of “diversity.” The program’s call for entries was cryptic: it was not some hollow celebration of diversity, but a poetic labyrinth that ranged in topic from deep sea divers to ghosts haunting old cantinas. When we received our readings to later discuss, an implicit thesis arose: neoliberal institutions had embraced the concepts of diversity and inclusion to the point of a revisionist absurdism; new liberatory concepts of coalition building would need to be established if any hope remained.

It was amazing that such a gathering could go so awry. Little to no facilitation on the part of the organizers inevitably meant that participants turned on each other, especially when considering the concepts of race and oppression discussed and the predominance of United States discourse. “We thought you would drink more mezcal,” one of the admins said nonchalantly, a statement that elucidated the wide gap between Mexican and U.S. university culture. So many American participants took it upon themselves to “save” the space, saying things like “I just want everyone to feel seen and heard,” or “we need to talk about race in this space.” It was a declarative coup: attempting to lay everything out on the table visually and verbally, and to figure it all out; to wade through the cacophony of distrust and unease and then put a period on the end of a nice sentence: everyone is welcome here.

It was clear to me that a gathering of foreigners in a colonial hacienda in rural Mexico was not much worth saving. “I’ve been a part of enough step-up and step-back processes to know when it’s time to step the fuck away,” my friend joked. So, I mostly walked away, preferring the meandering path of the dirty river. A week into the ordeal, multiple failed wifi zoom sessions with East coast university theory-heads, and all the boiled vegetable and fried tortilla enfrijoladas later, on one afternoon stroll along the banks, I found Canela. She was yelping as if they were her final desperate breaths, and she was almost black from all the fleas encrusted in her tan fur. I was already walking with a black and white stray who had adopted me for the hour, and even he pouted a look like he knew he had it alright. And I knew that if I picked this puppy up, I would be consenting to days, weeks, maybe months of responsibility.

“There’s a lot of savior energy here,” Marcelline, the only black participant at the symposium shot me a knowing look. I was aware of the optics: the who rescued who SUV sticker static in suburban traffic; after all, not two weeks prior, I was sending my friend—artist Vanessa Norton—inspired voice notes* about all the designer dog shit in gentrified Condesa, CDMX.

* a dog shit depature:

“Well,” I defended, “I saw an organism suffering, and I had to ask what was more emotionally draining: picking her up or walking away.” She wasn’t deterred: “I woulda said ‘life is pain,’ and kept on walking.”

So, I kept on walking: frail skeleton of a sagging dog on my forearm, calling out for the family living in the cinderblock shack back along the river. “Los otros dos cachorros murieron!” the young boy yelled towards me. With sunset in sight, I make a fast trek back to the hacienda to find my allies, fellow annoyed participants Divya and Hande. I took a collectivo taxi to get supplies—flea bath soap and puppy food—while they began their walk towards Tlaxco. That’s when they peered into a small altar and saw another one, smaller and maybe even more frail: Raj.

Canela and Raj, held by me, next to artist Hande Sever at the pulque hacienda once operated by the brother of Porfirio Díaz.

Raj when he was found inside the altar; digital photo overlaid.

We washed them near el rio with large bottled waters—Ciel, a Mexican brand owned by Coca-Cola. But, it was not enough water: they needed constant lathering to get the bugs out, most of which were dead, pasted onto their shallow fur in dried mud. I had to dunk them in the dirty river, letting the mystery mud dissolve back from where it came. It was the only option, not wanting to be blamed for any flea-infestations at the hacienda. There, we were grateful to the staff and the symposium admins that allowed us to keep and care for them inside. While they spent most of their time sleeping in an enclosed kitchen outside the suite, when they did stumble out to run on the dewy grass or use all their might to climb over cobblestones, it was, for many, a serotonin support-system. For others, it was an eye-roll, another odd element within a disjointed experience.

We learned from the veterinarian in Tlaxco that el rio was a dumping ground for anything people no longer needed. And, it was very common to find unwanted puppies along its mud and stone. Divya, Hande, and I joked that we shouldn’t take the river path back into town—we couldn’t handle any more than two. I still walked it everyday, considering what it would take to pick up another dying being or decide simply that life is suffering.

“Tiran de todo: basura, lavadoras, colchones y cachorros.”

They dispose of everything: trash, laundry machines, mattresses, and puppies.

II: dirty wet / (nothing but) flowers

with Vanessa Norton

Vanessa Norton has been developing relationships with waterways for over a decade now, traveling around the United States in her van, with an emphasis on the Western landscape, collecting containers of water from rivers, ponds, lakes, and oceans.

In doing so, she stumbled upon the New River / Nuevo Rio, made entirely of corporate pollutants and agricultural run-off, which flows 74 miles between Baja, Mexico, and Imperial County, California. It is the most polluted river in the continent, chemically speaking. She explains:

The New River was born after a Colorado River dam broke a century ago. It has since been fed by under-treated sewage, manufacturing wastewater, and agricultural run-off. These contributors result from the extractive “Free Trade Zone” practices of multinational export-based corporations in the area, governmental laxity on both sides of the border, and the siphoning of the Colorado River for agriculture. Attempts to clean up the river have long been deliberately underfunded. The river courses through communities where rural, low-income people currently live.

Norton’s artistic response to this crisis, a project called Dirty Wet, is not an environmental plea or campaign to clean up the waterway, but instead to pose the question of who and what societies, governments, and cultures are allowed to make dirty; who is allowed to be dirty, and who has the right to be clean. The New River is the mess of multinational greed, of not only biological environmental politics, but Foucauldian bio-politics as well: as Central American migrants are often crossing through this river in attempts to enter to United States, Norton was “attracted to the river as a place of convergence: accessible, polluted, liminal, a place where inside and outside meet and are confused.”

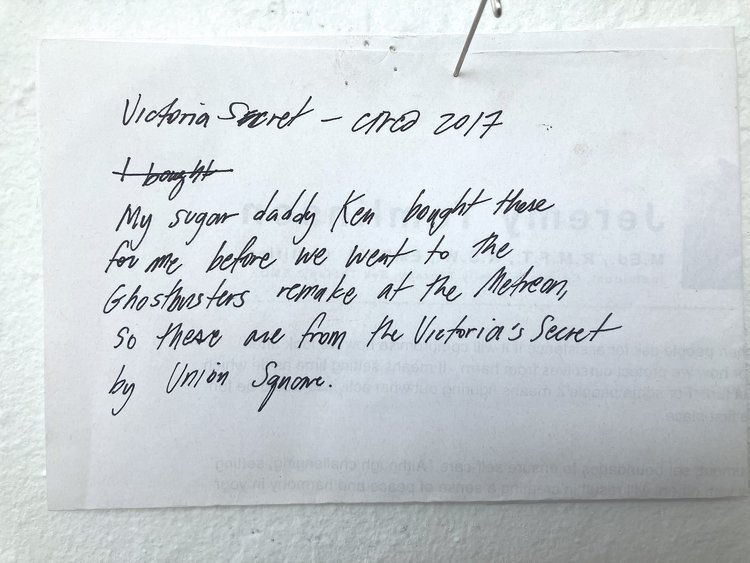

In considering the question of cleanliness, her answer is to make the river even dirtier: she has asked friends for pairs of used underwear with some accompanying note that explains its story, exciting or banal.

“Protagonists” by Vanessa Norton. Photographs of collected undergarments to be floated down the New River,

On five occasions, I traveled to the New River to float the underwear on the water's surface, documenting its travels and eventual immersion. I photographed these floats on a Holga camera using 120 film. I knew that I was doing nothing to purify the river. In fact, I was adding more pollution to it, but over time the floating underwear became for me an act of intimacy—complicated, as femme undergarments are, too, a place of so much convergence: gender performativity driven by erotic desire, but also as a liminal space, a swatch of fabric, in contact with the female body, where the inside and the outside meet.

Back in Xolostoc:

On the last day of the symposium, we are tasked with creating a stream of cultural activities for visiting “friends and family” of the organization. Some participants quietly protest the concept of putting on a show to other artists, curators, and funders, refusing to put on a happy face. “I’m so aware of the extractive labor organizations like this force artists to do on their behalf, and I’m not interested in consenting,” one participant told me between chewing another meal of boiled verduras and fried tortillas.

I propose a 45 minute walk along the river, but it is mysteriously erased from the program twice; I take this a sign that it ought to be forgotten.

informal map of el rio, from the hacienda to Tlaxco in a.r. havel’s journal

Instead, I ask a few participants for the shoeboxes they received with some leather boots purchased in town. I go back to Tlaxco again and spend $20 on some plastic tinsel, a little paint, and loose bits of red and gold fabric. I buy some “Canela” brand candies and chewing gum; and I go to work with a decade of experience as a bullshit carnival crafter, a jovial trickster ready to take the friends and family, on a parade around the hacienda for El Rey and La Reina.

I put my New Orleans friends’ band Wits End Brass on a portable speaker, and march around with some confused followers, the puppies bobbing up and down, fearing for their lives while the hacienda kitchen staff smiles and records it on their phones.

When the parade has commenced, the King and Queen are seated on a tabletop and I give a speech, commanding the “plebeians” of the space honor their monarchs and pay their taxes “in hard currency, only!” One curator from the United States hands me a 500 peso bill, admitting “I don’t know how much this is!” I tell her, “It’s like 5 bucks.” The King, the Queen, and the Jester: we make something out of nothing, cardboard boxes and some plastic litter, and we walk away with about $200 USD. Later that day, a visitor tells me “Your solo performance piece was really interesting.” I raise my eyebrows with an small eye roll and smirk: some people truly have no idea how to embrace silly joy.

Canela and Raj as “La Reina” and “El Rey” of the Hacienda. Photographer Jennifer Villanueva poses with them.

river, river, river

Shannon Stewart

documentation of “river, river, river” by Shannon Stewart | screaming traps. Judson Memorial Church, January 2020.